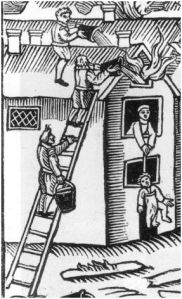

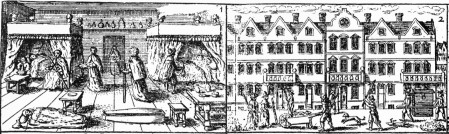

Two panels from a contemporary broadsheet (1665/6) showing the work of the Searchers who collected the cause of death data for the Bills of Mortality: in the lefthand panel they are present in a house afflicted by plague, while in the righthand panel the women walk the streets of London carrying their ‘wands of office’. [Nine images of the plague in London, 17th century]. Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0)

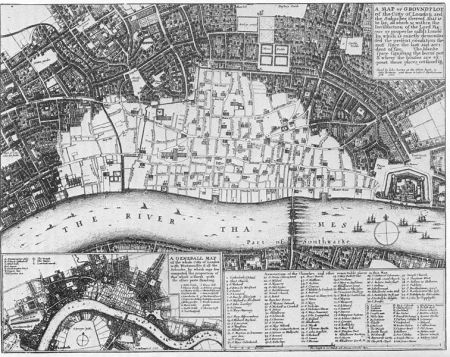

Rather than revelling in the massive numbers of plague casualties that the Bills stand witness to, and which are undoubtedly the most over-reproduced images of the weekly Bills across all types of outputs, I want to focus on the efforts that were made to identify and track the earliest occurrences of plague deaths. As we are all aware obtaining a true picture of contagion and associated death rates during an epidemic is far from easy – and it wasn’t easy for seventeenth-century Londoners either. But that is precisely what the Bills of Mortality were for.

The Bills, or at least the organised collection of cause of death information, was established at the end of the sixteenth century by the rulers of the City of London expressly to forewarn of plague. Clearly, my own use of Bills data, to support an understanding of early modern accidents, is tangential to this primary foundational purpose. While it’s possible to have some confidence in the accuracy of the Bills when reporting an accidental death, the veracity of the observations of the Searchers and the reporting by the Parish Clerks become more problematic during times of epidemic. Indeed, many early plague deaths remained unreported as such during the opening months of 1665 as London’s Great Plague became established. Whether this ‘failure’ was the result of corruption amongst Searchers and Clerks, misguided attempts to protect the character of their parishes and neighbourhoods, or simple incompetence/omission in a pressured environment is impossible to tell. Nevertheless, such failures, or the perception of them, came to taint the servants of this system through the eyes of commentators and later historians despite good evidence that outside of times of crisis the system worked well, albeit within the limits of early modern medical diagnostics.

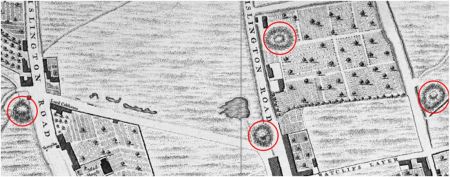

There is some evidence to support the belief that the presence of plague in London was appreciated, at least in governmental circles, earlier than the Bills report the first deaths. During April the Privy Council discussed events in St Giles in the Fields after the first households were shut up and which resulted in neighbours riotously ‘liberating’ the infected inhabitants. And by 12 May the King and his advisors had decided to form a special Committee of the Privy Council ‘to consider of the best means of preventing the spreading of the infection of the plague’. The most senior members of King Charles II’s court/government were to attend and they, in turn, called for expert guidance from leading physicians. Their most immediate instructions were for the obviously infected parish of St Giles in the Fields to enforce household quarantines and to set about building a new/temporary ‘pest house’ to help cope with the expected wave of infections.

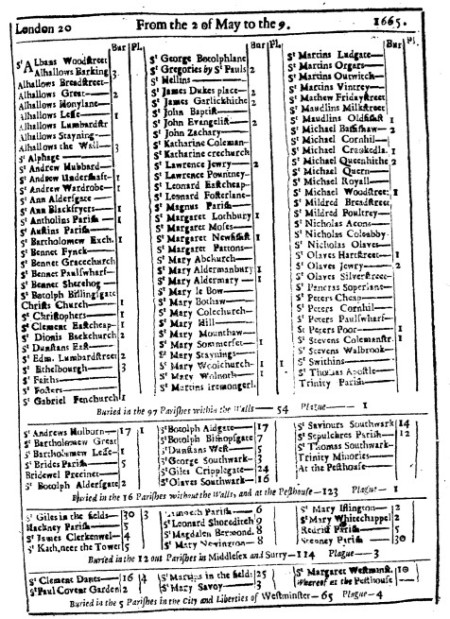

Private correspondence from the time also talks of the wider circulation of plague before it became an established feature of the Bills of Mortality. For example, during April and May John Allin, a former vicar of Rye in Sussex who was then resident in Southwark, noted in his correspondence that he ‘heard yesterday there are 2 houses shut up in Drury Lane for the sickness’ – this was on 27 April. In a perceptive comment he noted on 26 May that ‘ye bill mentioned 3 last weeke, and 14 this weeke, but its rather believed to be treble the number’.

Bill of Mortality for Week Commencing 2 May 1665 – London’s Dreadful Visitation: or, a Collection of all the Bills of Mortality for this Present Year [London: Printed by E[leanor] Cotes (for the Company of Parish Clerks), 1665]. Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0).

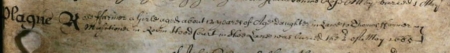

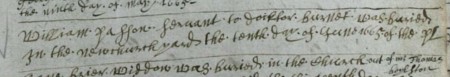

The St Andrew Holborn burial was however more emphatically noted as the parish’s first plague death. On 2 May ‘Rose Farmer, a girl aged about 12 years of age’ who lived in Robin Hood Court off Shoe Lane was laid to rest, her register entry being supplemented with an emphatic marginal note that simply read ‘Plague’.

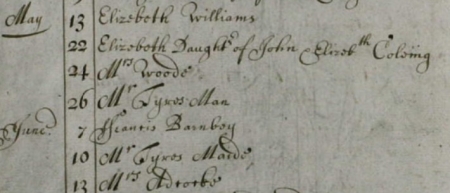

Burial Register for St Andrew Holborn: LMA P82/AND/A/010/MS06673 [1653-1672]

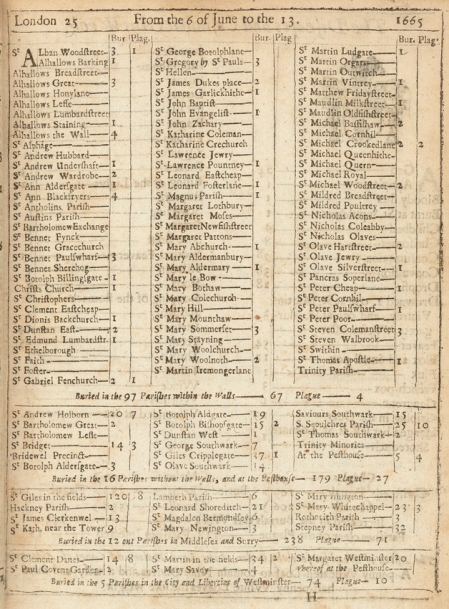

Bill of Mortality for Week Commencing 6 June 1665 London’s Dreadful Visitation [1665]. Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0)

Burial Register for St Alban Wood Street: LMA P69/ALB/A/001/MS06527 [1662-1786]

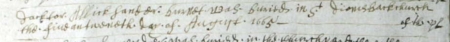

Burial Register of St Gabriel Fenchurch Street: Entry dated 10 June 1665 – LMA P69/GAB/A/001/MS05293 [1571-1709]

Burial Register of St Gabriel Fenchurch Street: Entry dated 25 August 1665 – LMA P69/GAB/A/001/MS05293 [1571-1709]

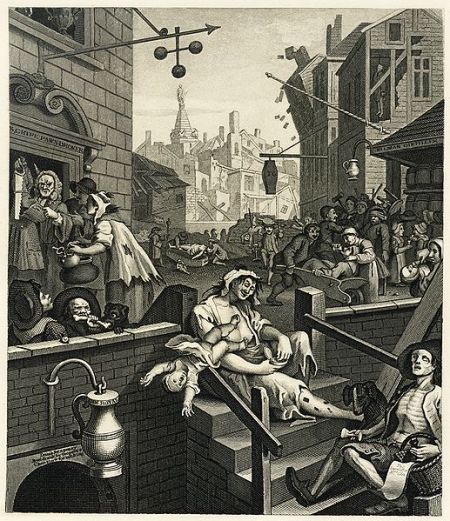

Several writers and historians have used the Bills of Mortality to illustrate narrative accounts of the Great Plague and, more recently, to critically analyse the origins, progress and eventual decline of the epidemic. Indeed contemporaries, those who lived through the trauma of 1665, also made good use of the Bills to help them make sense of the extraordinary mortality of that year. Among narrative accounts, two stand out: Daniel Defoe’s Journal of a Plague Year (published in 1722) and Walter George Bell’s The Great Plague in London (1924). A more recent and wider-ranging account can be found in The Great Plague (1999) and The Plagues of London (2008) both by Stephen Porter. For a more in-depth and critical discussion, attention should be paid to The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England (1990) by Paul Slack and London’s Dreaded Visitation: The Social Geography of the Great Plague of 1665 (1995) by Justin Champion.

The past provides a mirror against which we can consider our own actions and behaviours, from personal, national and international perspectives. The response to plague in the seventeenth century provides a number of surprising parallels to our current pandemic concerns – government emergency committees, self-isolation and quarantining, temporary ‘hospitals’, and the challenge of enumerating deaths and tracking disease spread (there is also a range of blaming behaviours which I haven’t had space to consider here but which in the seventeenth century were as equally flawed as those of the present-day). Nevertheless, such parallels are merely echoes from a different time, at once familiar and yet equally distant. What changes is the way we (or at least most of us) think about the crisis we face and how to cope with it as an immediate medical and social challenge, and the various paths we might follow going forward. History, and historians, can help us review, evaluate and where necessary challenge such responses now and in the future.