While few died in the making of this blank area on the map of London, many more were killed filling it in again.

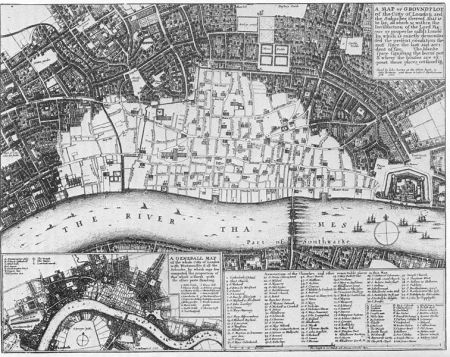

“How many people were killed by the Great Fire of London?” A question often asked and on the occasion of the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire a question which merits an answer. The first thing to make clear is that, despite the terrible devastation caused by the flames of September 1666 which resulted in the loss of more than 13,000 buildings, very few people directly lost their lives in the inferno. The initial response to the Great Fire was not to fight the conflagration but instead pack-up and run-away. Despite the ferocity of the fire it nonetheless moved slowly enough that most Londoners could simply take evasive action; having said that a small number of people did die as a direct result of being caught up in the flames.

Unfortunately one of the few gaps in the publishing run of the weekly Bills of Mortality occurs at the time of the Great Fire. The Hall of the Parish Clerks Company, located in Broad Lane in the riverside parish of St Martin Vintry, was an early victim of the fire. While the clerks were able to remove many of their possessions and papers they did not have time or resources to save their heavy and cumbersome printing press. The press was sacrificed to the advancing flames on the night of Sunday 2 September. As a result there was a four week hiatus in the production of the weekly Bills. When they resumed on 25 September they did so in a limited way only reporting on the sixteen and fourteen parishes of the City Within and Without the Walls that were noted as ‘still standing’. Importantly no attempt was made in the weekly output to provide an aggregated catch-up for the missing four weeks.

So the weekly Bills provide no record of those who may have died as a direct result of the Fire. But it seems the Parish Clerks did keep or gather some sort of tally of mortality for the month of September as the numbers reported as ‘burnt’ in the Annual Bill of Mortality for 1666 exceeds the total derived from the forty-eight weekly Bills that were produced during that year. A comparison of the two figures suggests that no more than seven Londoners died by being burnt by the flames of the Great Fire.

Walter George Bell in his account of the Fire, first published in 1923, estimated no more than six had been burnt. He provided details for four of these victims, drawn from various sources. These included the maid servant of Farriner, the baker, who was left behind in Pudding Lane; an old women who was burnt while sheltering in the shadow of the walls of St Paul’s; Paul Lowell an 80 year old watchmaker who refused to leave his house in Shoe Lane; and an old man who also perished at St Paul’s and whom Samuel Pepys informs us died when he returned to collect a blanket he had left there. In fact at the time there was a general belief that despite the devastation no-one had died in the Fire, a view that was communicated readily as a form of English miracle.

But is it fair to say that the Great Fire of London killed very few people? Yes if we are talking of the four days of the Fire itself, but certainly not if the human cost of those forced into homelessness or those placed in hazard by the Great Rebuilding is considered. While it is difficult to estimate how many of the City’s ‘refugees’ died through cold, hunger or disease in the immediate aftermath it is possible to enumerate deaths associated with the reconstruction activities.

The Weekly Bills of Mortality supply evidence for numerous construction-related deaths within the devastated area over the following decade or so. During that period at least 75 building workers died as they fell from walls, ladders and scaffolds, were struck by stones, timber and bricks, or were crushed by falling earth and debris, across a range of City construction sites. Elements of the death toll can still be linked to the Fire through to the end of the century if the slower process of rebuilding St Paul’s Cathedral and a number of the City churches is considered. At St Paul’s in particular workers were crushed by falling masonry or fell from the great heights of the walls, towers, pinnacles and dome.

So we, 350 years later, have a broad consensus that only a handful of Londoners died during the four days of the Great Fire in September 1666; but in April 1704 poor Widow Mullins might not have agreed with such an estimation as she accepted from the Commissioners for the Rebuilding of St Paul’s the sum of ‘£5 for her present subsistence’ following the death of her husband, a labourer lately killed on the cathedral works.