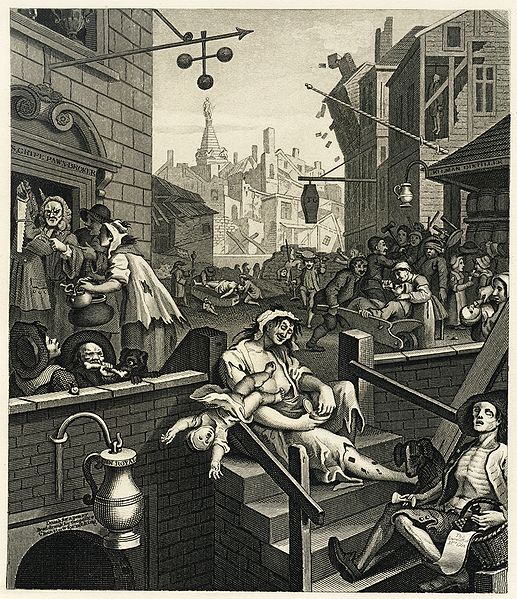

On 13 August 2025, BBC News reported the publication of a report by the UK’s NHS-funded National Child Mortality Database. The quote above is not, however, taken from that report. It is, in fact, from a letter sent to The Gentleman’s Magazine in January 1751. The anonymous letter writer expressed concerns for childhood deaths that occurred through accidental falls from windows and burns from stoves. Despite the nearly three hundred years that separate the report, the letter, and the deaths they encompass the circumstances remain tragically alike.

Between 1655 and 1735, the Bills of Mortality reported that 209 people died after falling accidentally from windows. The number of others who were injured but survived after such events is not known. Given the severity of injuries often sustained in falls from height, however, it is likely that most falls during the period proved fatal.

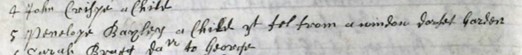

The sense one gets from reading associated evidence is that women and children were at particular risk. To give some examples, in late April 1657, a girl named Penelope Bayley fell from a window and died in Dorset Garden in St Bride’s parish south of Fleet Street.

The London Archives: P69/BRI/A/005/ MS06540/001 (5 May 1657)

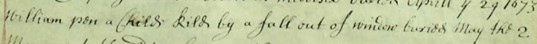

Also in late April, but this time in 1673, a child named William Pen died after falling out of a window in the City of London parish of St Katherine Cree.

The London Archives: P69/KAT2/A/001/MS07889/001 (2 May 1673)

In the parish of St Mary Newington in Southwark, a girl was reported, in the Bill of Mortality of 22nd October 1706, to have fallen from a window and died. While the parish register does not provide a cause of death, it is likely to have been Mary Austwick, daughter of William Austwick, who was buried on 24 October of that year.

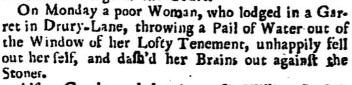

In a final example, evidence is derived from a contemporary newspaper, the Original Weekly Journal. In December 1717, it reported the death in the parish of St Giles in the Fields of an unnamed ‘poor woman’ who ‘throwing a pail of water out of the window of her lofty tenement, unhappily fell out herself’.

The BBC article notes the observation of Dr Noelle Mottershead, paediatric consultant at Manchester Royal Infirmary, that more children with window fall-related injuries presented in the first half of 2025 than usual. The implication is made that the exceptionally hot spring weather was to blame. This is a well-placed observation, as across the 75 years of Bills of Mortality evidence, the peak season for window fall fatalities was the spring, while the peak month was May (27 reports). Although detailed weather information is not available for the early modern period, it is clear that seasonally warmer days accompanied by ‘spring cleaning’ and associated maintenance activities likely encouraged the opening of windows that, in the preceding winter months, had been kept firmly shut.

There is yet another unsettling parallel between the concerns of the anonymous author of the 1751 letter and modern-day incidents: building technology. The letter in The Gentleman’s Magazine noted that ‘It is well known that many families in London are obliged to live upstairs, one, two or three stories … we hear of dreadful accidents by children falling through the windows, or by the sashes being lifted open, and the unhappy young things left (by carelessness) to gaze at … something’ falling out.

Sashes were a relatively new form of window in the early 18th century, though by mid-century they had become a common design element in newly constructed buildings across the metropolis. The author of the letter goes on to suggest fixing the lower sash in place and opening the upper would hinder many accidental falls, effectively proposing the functional equivalent of modern window restrictors.

Whether 300 years ago or today, children falling to their deaths from poorly designed, faulty, or improperly operated windows remains a concern. Contributing factors include the need for ventilation in poorly designed accommodation, especially during periods of hotter weather, and lapses in appropriate maintenance actions. Also, it is clear that while status might not be considered relevant in all cases, whether then or now, social deprivation remains a critical driver of many events.

Such deaths were, for the most part, avoidable then. Such deaths should be avoidable now. As the anonymous letter writer of 1751 observed, by the application of some simple measures, they were ‘fully persuaded that many lives would be saved’.